Powering our way to the future

There’s a long tradition of pioneering work at SCHOTT, but the company also relies on courage, curiosity, and passion for its first large-scale implementation of hydrogen in glass production. We spoke to the hydrogen experts leading this groundbreaking project.

By using hydrogen in glass production, SCHOTT is getting closer to achieving climate neutrality.

- In addition to electrifying its the melting tanks, SCHOTT is running a pioneering project to use hydrogen in glass production.

- SCHOTT is the first glass company to use hydrogen on such a large scale.

- The H2 Industries project is an important milestone for the company in the process of technological change and decarbonizing production.

Matthias Kaffenberger is restless this evening. He’s sitting on his sofa at home, updating an online portal on his smartphone, and is impressed by the curve on a chart that keeps building up. The chart documents the filling status of the hydrogen tank at SCHOTT’s Mainz plant, and resembles the recording of a seismograph measuring earthquakes.

Matthias is checking the final phase results of the company’s H2 Industries research project, and he’s not the only one hoping that nothing will go wrong in the home stretch. Despite perfect planning, there are many risks involved in this kind of a project, such as the weather not cooperating or a delivery getting backed up in traffic – factors he can’t influence himself.

For the melting tank to work effectively, the amount of hydrogen added to natural gas has to increase continuously, meaning that the tanker must deliver refills twice a day – something confirmed by the zigzag deflection on the chart. An interruption in supply could have fatal consequences, both for the experiment and for the glass melt, which cannot fall below a specific temperature.

Matthias can’t stand it any longer, so he drives to the plant and breathes a sigh of relief as he discovers the hydrogen supply has arrived just in time. The tank is refilled and the curve in the chart on his smartphone points upwards again. Everything is running perfectly.

“The hot phase was pretty exciting,” says Matthias with a smile.

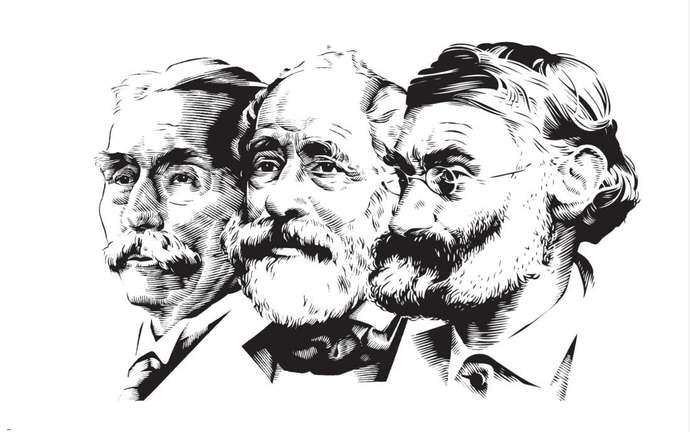

SCHOTT Pioneers

The list of pioneers at SCHOTT is long. The original pioneer, Otto Schott, not only founded the company but invented specialty glasses, paving the way for an entire industry. The quality of his optical and technical glass surpassed anything that had been produced before. In 1884, he set up a glass laboratory with Ernst Abbe and Carl Zeiss, which has been driven by the curiosity and innovation of its employees for almost 140 years under the SCHOTT name. Today, the company holds over 3,500 patents and employs around 700 researchers around the world who are working on future-proof solutions.

A model of sustainability

SCHOTT’s H2 Industries project is not only an important milestone in the company’s pledge to decarbonize in its production, but also a model for the entire industry. No other glass company has attempted to use hydrogen on such a large scale in its glass production. However, taking the road less traveled is a part of SCHOTT’s spirit, which consists of know-how, perseverance, and vision, as well as a lot of courage.

“We wanted to test it,” says Matthias about the project’s origins. “We wanted to act and not have to react when the provider enriches natural gas with hydrogen.”

After completing the test phase at the end of 2022, SCHOTT is seeing its first successes. “This large-scale trial makes it clear that more climate-friendly technologies can work in an energy-intensive industry,” says SCHOTT CEO Dr. Torsten Derr.

Pioneers at SCHOTT 2.0: The hydrogen project team from left to right Klaus Schönberger, Pascal Thomas, Jan-Ulrich Quade, Matthias Kaffenberger, Moritz Wolf, Stefan Schmitt

Matthias has planned this project with great care, leaving nothing to chance apart from traffic and weather. For him, perfect planning means a 3D laser scanner capturing information from 500 million points at different locations in the plant using 360-degree images to generate a realistic 3D map of the entire plant.

This visualization of the relevant project stations helps in developing various scenarios and project sequences. In addition, it helps simulating and determining the positions of tanks, containers, and pipes in advance. “We planned everything precisely and in detail,” says Matthias. “We even digitally recorded the smallest components, such as a burner. And in the end, we managed to match calculation and reality perfectly.”

Exploiting potential

When Matthias joined SCHOTT in April 2019, the topic of hydrogen was picking up speed, with project manager Stefan Schmitt having already laid the foundation. Within the Research and Development department, Schmitt first considered hydrogen in the initiator process, then proved its feasibility in the laboratory. Then, 2.5 years ago, a 90-liter tank was successfully operated exclusively with hydrogen in the pilot plant.

“If that worked at 100%, then there was a good chance it would work at 35% in the large tank,” explains Stefan. “But we have more than 150 different glasses, so we had to test how far we could go with the existing system in a large-scale test. Our goal was to harness the potential of hydrogen for the future.”

Even if SCHOTT could used just one-third of hydrogen and realized the associated natural gas savings, its carbon emissions would be reduced by 14%.

A symbolic tank

Despite intensive preparation, the hydrogen project has been a roller coaster ride, with unexpected twists and turns, a fast pace, and emotional ups and downs. But innovation rarely follows the straight and narrow. “I often came into the office after meetings and said, ‘Okay, let’s drop the project,’” Matthias recalls.

Christine Kraus, who shares an office with him, understands the emotional roller coaster. She planned the 500 meters of piping through the plant, which involved highly detailed work, such as ensuring the tightness of the copper pipes. But the more obstacles the team had to handle, the closer it brought everyone together.

A milestone with symbolic value was the hydrogen tank’s installation at the end of September 2022. The 21-meter high tank with a diameter of 2.8 meters was maneuvered through the plant by truck, then placed using a jib crane. Unfilled, it weighs 47 tons and can hold 500 kilograms of hydrogen. “Hovering the tank and the spot-on landing was like a perfect production at the ballet,” enthuses Matthias.

When the tank was finally in place, one and a half years of planning came to fruition. Jan-Ulrich Quade remembers this moment, as well as the months before. As head of environmental protection technology, he rifled through a lot of plans and expert reports in the run-up to the project. “We had to run through scenarios for all eventualities and define what would happen,” Jan-Ulrich recounts.

This was a mammoth task with a limited time window, with general operator obligations, alarm, hazard prevention plans, monitoring systems, notification procedures, and transitional regulations. It’s not without reason that Jan-Ulrich calls himself “an office tiger.”

What is hydrogen?

Hydrogen is a chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. It is the smallest and most abundant element in the universe, and when combined with oxygen, it can easily self-ignite. The colorless and odorless gas is found on Earth almost exclusively in the bound form, in fossil raw materials such as natural gas, crude oil, and more than half of available minerals.

Hydrogen is carbon-free only if it is produced exclusively with green electricity, which is the case with green hydrogen. Using electricity from renewable sources, water is split into hydrogen and oxygen in an electrolysis process. Green hydrogen could play a fundamental role in the energy transition in transportation and industry. However, hydrogen is expensive and needs to be available in sufficient quantities for industrial use.

When the project starts, Jan-Ulrich is also standing by the tank. Over four weeks, around ten tons of hydrogen will be needed. Initially, the tanker truck drives up every other day, then daily, and in the end, even twice a day, for a total of 27 deliveries. Messer Industriegase GmbH from Bad Soden near Frankfurt ensures the supply runs without interruption. “We could rely on them, which was ideal,” says Matthias.

Since the pressure in the tanker truck is 200 bar – higher than in the installed tank – the exchange runs on its own via pressure equalization using two small tubes the size of a garden hose. Refueling takes just over an hour and soon becomes routine. The hydrogen then ends up in the mixing container via the pipe system laid especially for the project.

The path to climate neutrality

SCHOTT is pursuing the goal of decarbonizing its production step by step (Scope 1+2 GHG Protocol) in its production. To achieve this, it relies on an action plan with four pillars. A significant milestone was reached at the end of 2022 with the switch to 100% green electricity and the reduction of global CO2 emissions by 60%. However, since manufacturing specialty glass requires a lot of energy, SCHOTT is also working to implement technological change. Therefore, SCHOTT is pursuing two goals with numerous research projects: the electrification of the melting tank based on green electricity and the use of hydrogen, with a long-term goal to replace fossil fuels entirely.

The German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action is supporting two projects with a €4.5 million grant to enable the company to operate furnaces electrically in the future. One project concerns the melting process for pharmaceutical glass, and the second concerns the melting process for specialty glass for technical applications. Another field of action is the improvement of energy efficiency, and compensation of the remaining emissions with certificates from high-quality climate protection projects.

The container made of sheet metal is 8-meters long and 2.5-meters wide. Unimpressive from the outside and unspectacular from the inside, natural gas and hydrogen tubes come together at the front and the two gases are swirled through a static mixer.

Christoph Neeb keeps a close eye on anyone who approaches or enters the container. The employee from Mainzer Netze GmbH is in charge of the project, and uses a “sniffer” to check for highly flammable hydrogen in the air. “This is also a significant project for us, where we are learning a lot,” he says.

“We haven’t had even a single malfunction.”

The network operator’s container, which supports the project as a partner, stands in the middle of the plant in front of the brick building where the tank is located. As well as a change of location, there’s also a change in temperature. Just two doors, three flights of stairs, and a few meters of walking sees the tank interior go from near-freezing to 1,700 degrees Celsius.

If setting up the tank is like a ballet, then the first tank test is the furioso finale. Moritz Wolf stands at the control unit while Matthias starts the admixture via the touch display on the mixing container. Moritz has been at SCHOTT since 2016 and, together with Georg Demmer as line manager, has created the conditions for implementing the project at the tank. “We did some conversions and installations, which was quite a technical challenge,” the 36-year-old explains.

The messages from around 4,000 measuring points arrive at the melting tank’s control system, with Moritz conducting the controls that influence the burner settings. Since hydrogen has a lower heating value than natural gas – three-kilowatt hours to eleven-kilowatt hours per cubic meter – good advice is a matter of calculation and ingenuity.

“We would have gotten a lower heating value with the same flow rate, but we need consistent energy,” Moritz remembers. “If we add hydrogen, we have more volume with the same energy input.”

The pressure was ramped up to bring more volume into the tank at the same flap position. “It worked,” says Moritz.

The H2 Industries project

The total cost of the research project is more than €714,000. The Rhineland-Palatinate Ministry for Climate Protection, Environment, Energy and Mobility has provided around €338,000 in grant funding from European Union resources under the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF). The project partner is Mainzer Stadtwerke AG. Mainzer Stadtwerke provides SCHOTT a mobile blending station to generate the natural gas-hydrogen mixture for the test program.

Matthias is also surprised that the detailed preparatory work paid off. “We had prepared for troubleshooting, but there were no malfunctions,” says the 44-year-old. “Everything went as calculated and predicted.”

The project runs like clockwork for four weeks. In three trial phases lasting about ten days, the admixture of hydrogen is increased to 35% and maintained. “I’m glad it worked out so well,” Moritz says. Matthias adds: “This was the most exciting project I’ve supervised.”

The future of hydrogen power

So what’s next? The trial has shown that the addition of H2 is technically possible. “Through our hydrogen study with a roadmap, we have created the basis for measures for the state’s hydrogen strategy and an important contribution to climate neutrality,” said Katrin Eder, Minister for Climate Protection, Environment, Energy, and Mobility for Rhineland-Palatinate. “Hydrogen is a central building block for the state government’s goal of being climate neutral by 2040. SCHOTT is a pioneer and role model for the energy-intensive industry in Rhineland-Palatinate.”

In 2024 the H2 team reached another significant milestone, as the experts succeeded in melting optical glass using 100 percent hydrogen, marking a first in the specialty glass industry.

This achievement earned SCHOTT an innovation prize supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research – a recognition that project lead Lenka Deneke celebrates as a “confirmation that we took the right step.”

“The award brings recognition for our company,” she says, “but it is also a thank you to all the colleagues who were involved, who helped to shape it and who were always curious.” The successful outcome of the trial highlighted the company’s pioneering spirit and commitment to sustainability, with the hydrogen-melted glass passing initial quality checks without any noticeable deviations from natural gas-melted glass.

Successful testing on a large industrial scale: SCHOTT has produced an optical glass with 100% hydrogen for the first time. Photo: SCHOTT

Inspection of a glass bar: The large-scale test received excellent marks, and the quality of the glass is now being analyzed.

Despite the project’s success, the hydrogen initiative is still facing many challenges due to the lack of necessary infrastructure for long-term implementation. Although the project’s early stages confirmed hydrogen’s technical feasibility, H2-expert Matthias Kaffenberger explains that the next step – longer trials on larger furnaces – would require extensive infrastructure like pipelines, which are currently unavailable.

“Technically, we would be able to do this thanks to our preliminary work,” Matthias says. “But we would need a massive hydrogen supply at a competitive price level. This would require regulations, pipelines, network operators and much more infrastructure that simply does not yet exist.”

SCHOTT will therefore focus to using electricity to heat glass-melting tanks. However, the company remains actively involved in hydrogen infrastructure development through initiatives like H2erkules, as they await future availability of green hydrogen.

The project may have ended for now, but SCHOTT’s contributions set a strong foundation for future adoption of hydrogen in industrial applications.

“We were very early but not too early,” Matthias says. “And we have no doubt that it was the right step to take.”