Mirroring nature’s most powerful protection

What does amber pharmaceutical glass tubing have in common with hippos from Asia? During their visit to the Shanghai Wild Animal Park, two specialty glass experts make an unusual discovery.

Two glass experts discuss how to protect light-sensitive drugs from sunlight.

- Amber-colored borosilicate glass resembles the natural sunscreen of hippos and effectively protects light-sensitive drugs.

- The amber glass meets stringent quality requirements for pharmaceutical packaging and prevents chemical interactions with the drugs.

- These findings contribute to the safe packaging of medicines for a healthier future.

Every second of every day, the Sun bombards the earth with trillions of watts of energy in the form of infrared, visible, and ultraviolet light. As the primary source of energy for our home planet, this magnificent display of power becomes something of a revered deity. It both creates and destroys. Life on Earth depend on the energy emanating from the Sun – but too much can cause irreparable harm.

This is the discussion between Dr. Folker Steden and Jocelyn Jiang, who work with specialty glass but draw inspirations from all scientific disciplines. Today, they are intrigued by research published in Nature magazine about how hippos beat the burn.

Researchers found that hippos can secrete “sweat” that oxidizes to appear red and then polymerize into an amber-like color. Thus, researchers hypothesized that these pigments protected the hippos fragile dermis from being damaged by too much radiation from the Sun. Scientists analyzed the secreted substance and found these pigments absorbed light in the UV and short-wave visible range.

In the spirit of science, Jocelyn and Folker decide to make an unusual visit to the Shanghai Wild Animal Park and see this phenomenon with their own eyes. Although early in the morning, this is a typical summer day in Shanghai with over 30 degrees Celsius and a high UV index – a level of radiation that the National Weather Service considers strong enough to damage the human skin. To an uninformed onlooker, the hippos seem to “bleed” from UV damage to their skin. But the truth is quite different – the pigmented “sweat” is a natural form of protective sunscreen.

Jocelyn and Folker cannot help but draw a parallel their own area of expertise: what is the most powerful protection against sunlight for human health?

The science of light and colors

Research has shown that melanin-based traits play an important role in biological responses to ultraviolet radiation, including in human skin. "In essence, pigments can prevent damage caused by energy to key chemical molecules, including proteins and certain organic substances,” says Folker. “Light-sensitive substances have unstable functional groups. Energy from sunlight can cause the weak chemical bonds in the functional groups to react easily, which results in a loss of molecular function."

Many antibiotics and important medications, including medications that treat cardiovascular diseases, require protection from light. Derivatives of the drug Nifedipine have a photo-chemical half-life of only a few minutes. Vitamins are also well-known photosensitive substances that play an important roles in human growth, metabolism, and development. Degradation under light adds a layer of risk to patients who require safe and reliable storage of vitamins that supplement their care.

“In the realm of human health, we also aim to create the ‘sunscreen effect’ but in an inorganic way,” says Folker. The color of the glass tubes can be fine-tuned by adjusting the proportion of additives, wall thickness, heating temperature, and other parameters. Adding iron oxide and titanium oxide to glass, for instance, can create amber glass, while adding iron oxide-manganese oxide makes green glass.

It was over a century ago when German scientist Otto Schott first used amber borosilicate glass for pharmaceutical packaging that came directly in contact with drugs. Where hippopotamus’ “sweat” functions to protect its skin against the sunlight, amber glass absorbs ultraviolet and shortwave visible light to protect photosensitive drugs. Different from non-pharmaceutical colored glass (such as the ones used for packaging beverages, cosmetics and other content), pharmaceutical amber glass quality requirements have yet another specification: The limitation of transmission of electromagnetic light in the range of UV.

“The amber glass for the manufacture of pharmaceutical containers for parenteral drugs is Type I borosilicate glass. Injections enter the bloodstream directly while oral medication passes through the digestive tract and stomach first. Therefore, the standard for parenteral glass containers is much higher than that for oral drug containers," says Jocelyn.

Protecting human health for a sustainable future

For everyone on planet Earth, health is an important pillar of life and the basis for the long-term development of the economy and the society. The United Nation has defined Good Health and Wellbeing as one of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to transform the world. Thanks to science and technology, our society continues to make progress in our ability to fight against diseases and enhance our health.

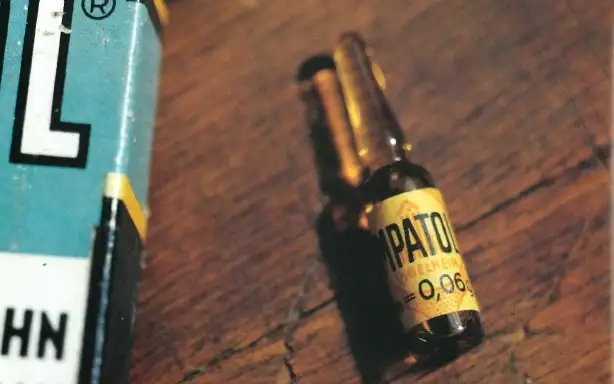

Expired? Not with specialty glass!

In 1989, a Mainz resident was sorting through belongings from his aunt Rita when he came upon an old medicine cabinet. He handed it over to a pharmacist, who discovered a brown bottle containing Sympatol. Produced 50 years ago by Boehringer Ingelheim, a leading German pharmaceutical company, this adrenaline derivative is still used to treat acute heart problems. When the news spread to Boehringer Ingelheim, out of curiosity, they tested how the medication had held up. To their surprise, the test showed that it was still > 98.8% effective. The raw material that packaged this medicine was SCHOTT FIOLAX® amber borosilicate glass. In the letter from Boehringer Ingelheim to SCHOTT, they expressed their excitement: “50 years old and almost as fresh as on the first day. It's not every day that we witness quality like this."

The two specialty glass experts Jocelyn and Folker had an inspirational day at the Wild Animal Park. Jocelyn says: "I am not sure if the person who first used color to shield the sunlight was inspired by the hippopotamus. We rely on science to discover and utilize the laws of nature. And this is, in my opinion, a sustainable concept. But I know for sure that although nature gives us challenges, it also shows us the solutions."