AR’s big breakthrough is hidden in the lens

After years of false starts, the future of augmented reality may depend not on chips or software, but on how light moves through glass.

A new class of glass-making engineered to control light with extreme precision has opened the door to AR’s next breakthrough.

- AR has long struggled with bulk, limited brightness, and high power use.

- Geometric reflective waveguides use embedded mirrors in the lens to direct light.

- Now manufacturable at scale, this technology marks a turning point toward truly wearable, consumer-ready AR.

Long before engineers chased the promise of digital overlays, Benjamin Franklin grappled with the problem of human vision. By 1784, having grown tired of fumbling between two pairs of spectacles to manage blurred near and far sight, the youthful 78-year-old searched for a solution.

While a few inventive opticians had experimented with more elaborate frames, Franklin’s answer was deceptively simple. He sliced the lenses from both pairs of glasses and combined them into a single frame. In a letter to his friend George Whatley, he wrote that he was “happy in the invention of double spectacles, which serving for distant objects as well as near ones, make my eyes as useful to me as ever they were.”

Those “double spectacles” would soon be known as bifocals, a creative tweak to glass lenses that changed the way people moved through the world. Centuries later, a unique rethinking of lens-making would again provide a breakthrough in human vision – but this time, for augmented reality.

The pioneer behind modern optics

Nearly two centuries after Benjamin Franklin combined two pieces of glass to create bifocals, a German glass chemist named Marga Faulstich redefined what lenses could be made from in the first place.Joining SCHOTT in 1935, Faulstich co-developed thin glass coatings that became foundational for sunglasses, anti-reflective optics, and modern façade materials. Over four decades, she rose to become SCHOTT’s first female executive and helped create more than 300 specialty glasses, including the lightweight corrective lens Schwerflint 64.

In many ways, her pioneering work in glass chemistry and optical performance paved the way for today’s AR waveguides.

Technology at the precipice

For decades, engineers have chased the dream of turning ordinary eyewear into intelligent companions: glasses that could layer digital information seamlessly onto the world around us.

Yet the technology long lingered at the edge of possibility. Even as microchips shrank and designs improved, augmented reality (AR) or mixed reality (MR) remained caught between promise and practicality. Early iterations were too clunky, power-hungry, or lacked the supply chain for mass production.

After years of prototypes and false starts, the breakthrough that could finally make smart glasses feel natural isn’t digital at all – it’s material.

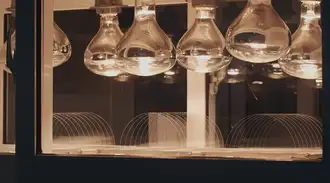

Evaluating waveguide prototypes in consumer-style frames – a key milestone in translating the technology from research to manufacturable AR devices.

At first glance, the lenses above might look like ordinary pieces of glass. But embedded in the lens is a cascade of microscopic mirrors – each one precisely angled to guide light from a projector in the temple through the glass and into the wearer’s eye. The result is an image that appears to float naturally in space, seamlessly blending with the real world.

Historically, AR lenses – or waveguides – have relied on “diffraction” to project digital information into the user’s view. These “diffractive waveguides” rely on a system of nanostructures, called “gratings,” that direct light by bending and splitting it.

Another optical system directs light via controlled reflection, not diffraction. These mirror-based magical lenses are called geometric reflective waveguides. That distinction, says Dr. Ruediger Sprengard, Head of Augmented Reality at SCHOTT, is what sets reflective waveguides apart.

“Reflective waveguides maintain brightness and clarity while using less power,” he explains. “They enable the kind of immersive, all-day wearable experience the AR industry has been chasing.”

This system also solves one of AR’s oldest design challenges: how to keep glasses lightweight. Rather than using external diffractive layers, engineers embedded the reflective architecture into the glass itself – a shift that enables lightweight, wearable technology while preserving both clarity and field of view. Achieving that delicate balance depends on nanometer-level precision at every step of production.

From molten sand to microscopic mirrors

Every waveguide begins with sand – quartz fused with select metal oxides and melted at around 1,600°C (2,912°F). The molten ribbon of glass then cools in a carefully controlled process known as annealing, which can take several weeks. Even microscopic inconsistencies can scatter light, so precision is measured at the atomic level.

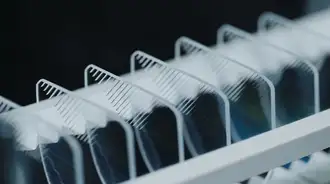

Once cooled, the glass is processed into ultra-flat optical wafers with precisely controlled surfaces. These optical wafers are then prepared for cleanroom processing, where they receive advanced coatings that transform them into semi-transparent mirrors – the foundation for augmented reality’s most sophisticated optics.

“You’re not just making glass. You’re sculpting how light behaves inside of it,” Ruediger explains. “To that end, our expertise isn’t only in making optical glass, it’s in processing and scaling in order to reach mass manufacturing.”

As the first company in the world to scale geometric reflective waveguides to serial production, Germany-based technology group SCHOTT’s full vertical integration ensures consistency, accelerates production, and makes next-generation AR smart glasses commercially viable.

“In order to achieve serial production of geometric reflective waveguides, design and scaling manufacturing had to evolve hand in hand,” Ruediger continues. “Every layer, every reflection path, had to be understood in both optical and material terms.”

A focus on the future

Franklin wasn’t chasing spectacle – he was solving a problem. In much the same way, today’s engineers are refining AR lenses not for sake of novelty, but for utility. It’s a continuation of the same impulse: to make our tools feel less like technology and more like extensions of ourselves.

“For years, the promise of lightweight and powerful smart glasses available at scale has been out of reach,” says Ruediger. “By offering geometric reflective waveguides at scale, we’re helping our partners cross the threshold into truly wearable products.”

Breakthroughs like these bring AR closer to something ordinary, reliable, and human – a tool that simply works, as Franklin might have put it, “to make our eyes as useful as ever they were.”